Microplastic pollution in cave sediments: ideas and methods for a baseline survey in the UK and Ireland

It’s been a while since I last wrote anything on here. Lots of other things have been distracting me (I’ll write more about these soon!), but I have had a bit of time to think about microplastics in caves a bit more since my blog post introducing the concept in May. Hopefully that summed up why we need to do some work to understand the problem of microplastic pollution and why the cave environment would be an interesting area of future study. Some questions I suggested could be answered by surveying microplastic prevalence in caves were:

-

to what degree are microplastics present in the cave environment, and how abundant are they at different scales?

-

what are the sources of microplastic contamination in the cave environment, what kinds of microplastics are present, and how do these sources change depending on the specifics of the site being studied?

-

how are microplastics dispersed through particular cave sites, and what can we say about the reasons for any patterns in dispersion that exist (for example, aquifer geometry or the nature of recharge to the cave system)?

-

to what degree is the epikarst able to filter microplastic from dripwaters and in what way does the presence of microplastics affect the biological and chemical functioning of the epikarst?

-

do cave microplastics harbor pathogens and pollutants?

-

have cave biota been affected by microplastics, and if so how?

This is obviously a huge amount of ground to cover, so it will be necessary in the first instance to focus on establishing a baseline of knowledge about the nature and distribution of microplastics within the cave environment. The aim of this survey would be to answer the first two questions in the above list for a series of cave systems across the UK and Ireland.

I have been doing some thinking about specifically how such a survey would be best carried out. Some basic guiding principles that I would like to stick to in such a project would be as follows:

-

Accessible: I really want anybody within the caving and cave science community to be able to contribute to this project. This could be via collection of data in their local caves; processing the samples; maintenance of project samples and equipment; writing up the results; and dissemination of the results within the community. Science should be easily accessible to everyone in society and at present this isn’t really the case with cave science in the UK.

-

Simple: As microplastic prevalence in the cave environment has not yet been formally studied and documented, there are a lot of low-hanging fruit to be grabbed in this area. Therefore, there is absolutely no reason to make this study overly complicated. Keeping it simple will ensure that anyone who wants to take part can do so without needing much specialist knowledge or equipment.

-

Cheap: I have no funding for this project yet (though I am working on this). So any project needs to have low overheads. Low costs also mean that the project is more likely to adhere to the previous two principles.

-

Decentralised: To reduce the workload on any one person (me!) and to ensure that the caving community feel engaged in the project, a distribution of responsibility across all involved in the project is desirable.

With all this in mind, I was really lucky to find a similar project studying microplastics in rivers in Scotland, led by a woman called Rachael Hughson-Gill. I first noticed her project, done as part of her masters at University of Glasgow and Glasgow School of Art, at the virtual EGU online conference in early May, and was super-impressed. See her conference display here.

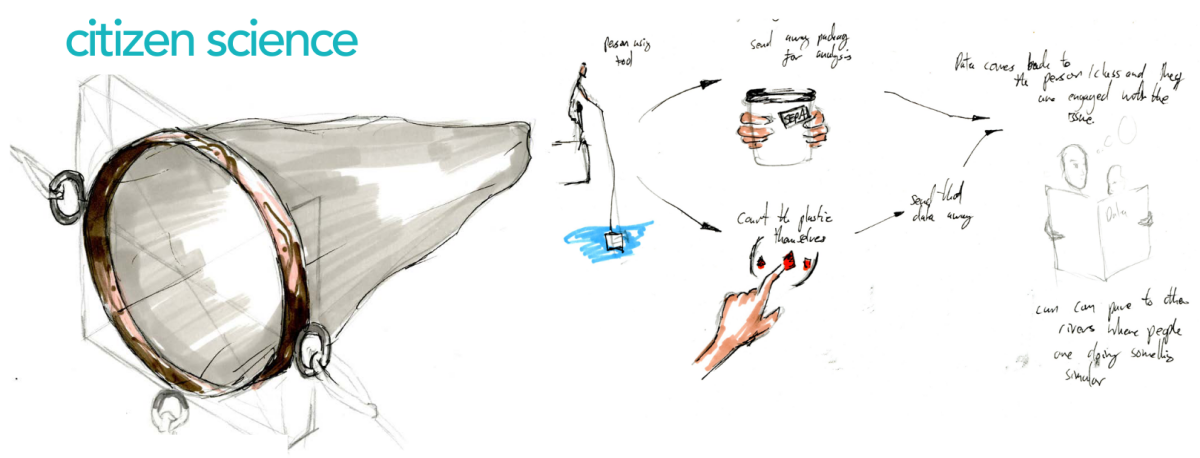

Essentially, Rachael’s idea was to engage with citizens, especially school-children, by designing a cheap method and equipment setup for them to take to rivers and perform spot-test sampling of microplastics themselves. A simple, low-cost vessel to capture the water was designed and distributed to citizens along with Whatman filter papers. At river sites, water collected in the vessel was filtered on-the-spot and then microplastic fragments on the paper were counted using a macro-lens of x10 magnification which can be attached to a smartphone. The total fragments counted were then added to an online user interface, allowing location, date and microplastic count to be recorded simply and quickly in a decentralised way. I’m very grateful to Rachael for the time she spent explaining her project to me over zoom and for her advice as to how to set up this project.

Sketch from Rachael’s EGU display summarising the concept of her project.

Sketch from Rachael’s EGU display summarising the concept of her project.

However, I’m going to propose that for this study we return to where microplastic contaminant research really began by focussing on sampling sediments rather than water. The first study on microplastics done in 2004 (by the man who coined the term ‘microplastics’, Richard Thompson) sampled sediments from several beaches and estuaries around the UK using very simple methodology to separate microplastics from sediment according to the contrast in density between them. They did this by creating a high-density fluid using a concentrated saline solution to separate the microplastics from the sediment; on stirring, the microplastics went into suspension in the solution whilst the sediment stayed at the bottom. They then filtered the resulting solution using a Whatman filter. The filtered samples were then dried and examined under a microscope. This simple method of density-separated decantation of microplastics from sediment is now reasonably common, though as I noted in the last blog there are still an array of possible methods in use.

That’s not to say that data for microplastic prevalence in cave waters wouldn’t be useful; quite the oppoisite! In practice there seems to be little difference between the methods for processing of water and sediment samples in terms of simplicity. The main difference lies in ease of transport of the samples from the cave, and the ease of obtaining a representative sample. Sediments can be simply dug up, with the required volume of sediment transferred into a metal container with a lid (not a plastic one to avoid any sample contamination), with all separation being done at a later stage.

By contrast, water is usually sampled for microplastics by using some kind of net to filter the water in situ, rather than a full representative sample being removed from the cave. However, a number of studies have found that this method is prone to under-representing the prevalence of microplastics, as the filters often do not capture nanoplastics, which are plastic particles smaller than 1 μm. Therefore, I feel that an initial focus on microplastics in cave sediments will not only be simpler logistically, but may also provide relatively complete picture of what kinds of microplastics are present in caves which is easy to understand.

So, we need a simple and robust way of collecting and processing cave sediments to understand their microplastic content. After a bit of looking around, I found a really excellent-looking device named the ‘Sediment-Microplastic Isolation (SMI) unit’, developed by researchers at the Plymouth Marine Centre as described in this paper.

The Sediment-Microplastic Isolation (SMI) unit. On stirring, sediment sinks to the base of the device, below the ball valve; microplastics and organic residue float to the top of the fluid column (in the headspace). The foil hood minimises contamination.

The SMI unit is constructed from 63 mm diameter PVC pipe with a PVC ball valve. The unit works by using the density separation principle of the initial microplastic studies to float the microplastics in a high-density solution. The microplastics rise to the top of the fluid column and the sediments settle at the base. A ball valve in the centre of the device then seals off the sediments and the upper section (the headspace). Fluids in the headspace are then filtered, placed in a sealed petri dish and analysed under the microscope later on.

The device requires sediment sample sizes of around 30 - 50 g (not much sediment at all). The overall cost per unit was £50 - £60, with the cost of the salt to produce the supernatant varying depending on the supernatant being used (around £12/kg for sodium chloride and £35/kg for zinc chloride). The study found that zinc chloride solutions with a density of 1.5 g/cm3 were the most effective at separating a full range of microplastics from sediments of a range of grain sizes (at high solution densities, fine sediment particles remained in solution as well as the microplastics).

Now we have a simple device that could be cheaply constructed in-house by the project, creating units on basis of need (start with a few, make more as the project grows). But where would be best to process the samples? Even with the light, durable design of the SMI unit, the necessity to bring along supernatant solution and also to clean the device between samples and before each use with purified water to minimise contamination means that on-site processing is likely impractical. It makes more sense to remove the samples from the cave environment in metal containers and then process them later on in a lab.

If this were the case, then we could have a gathering of anyone who had collected samples at a willing venue where the samples could be processed and analysed on the day by attendees. Only very basic lab skills (preparing the supernatant, adding to the SMI unit, stirring and filtering then analysing under a microscope) would be needed and very minimal equipment: this could even be done in a caving hut (when they eventually open again!). If a large enough sediment sample was taken from each location (say 0.5 kg) then several repeat analyses could be done by different people to get a representative measure of microplastic abundance and type. An amount of sample could also be saved for different tests later on. This use of resources would maximise scientific output and involve more people, thus broadening the reach of the project.

In summary, I think the basic steps for the project would be as follows:

-

Purchase raw materials (metal containers with seal to transport microplastics from cave, trowel, a few kilos of salt, some plastic piping and ball valves, micropore filters, petri dishes).

-

Go into some caves (determined by where those interested in contributing are based) and take some sediment samples. These can be stored at home by the samplers until a time when processing can occur).

-

Construct some SMI units.

-

Once enough samples and SMI units are available, arrange a time and venue for sample processing. Process and analyse samples for microplastic content and type.

-

Interpret and write up results.

-

Publish results.

-

Repeat!

I think the approach I have outlined will allow the project to be accessible to any caver (or citizen scientist), is simple and relatively cheap, and allows anyone involved to operate reasonably autonomously. I am planning to write a grant application to the British Cave Research Association to obtain funding for material and possibly transport costs via their Cave Science and Technology Research Fund (CSTRF). If anyone would like to collaborate with me on this then please drop me an email. Likewise, if anyone sees any potential flaws or issues with my ideas or wishes to contribute in any way I would certainly appreciate your input. Psyche!

Some very muddy diggers (including me, centre) in a periodically active sump at Telegraph Aven, Goyden Pot, Nidderdale, 2017. We’ve probably left a lot of microplastics in here ourselves, but were there any here before we began digging out the sump? And can any microplastics transported there by water be distinguished from microplastics brought in by cavers? Let’s find out… Photo: Nick Bairstow.